Good weather for ghosts

Ghosts: a picky lot. Particular, I think is the word, and conservative in their tastes. This is most evident in the places they choose, by all accounts, to hang out. Open-plan offices are not really their thing. Nor leisure centres. In fact, their architectural preferences have a lot in common with those of Prince Charles: give them a bit of thatch and some original half-timbering, give them an attic or even better a cellar, and they are happy. Provide mood lighting and that’s it, really, you have a ghost magnet.

Except often, weirdly, you don’t, and today’s blog, at this chill midwinter season, is about why. Why do some places that seem to fit the ghost bill, that have all the ingredients to be dark and spooky and atmospheric, turn out as dull as doorknobs or dishclothes or anything else domestic beginning with ‘d'; while others, not apparently so dissimilar, prove themselves crowded and numinous, full of a trembling sense of half-terrified wonder, of mystery, of a thin veil between this world and the next?

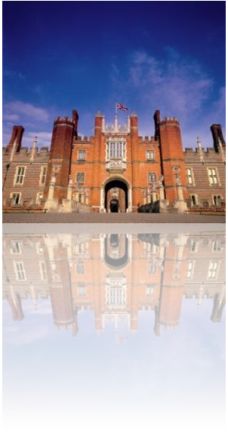

I started wondering about this question while writing Central Reservation, a ghost story of a kind, and while working for a charity that looks after the Tower of London and Hampton Court Palace. In my writing, I was trying to evoke a sense of the haunted, and what haunting places can do to those who live in them (though since for me the most haunted of places is a quiet country lane, down which people have trod for centuries, my haunted places tended to be outside).

Now in theory, you’d think that both workplaces would have provided useful material for this. The Tower, a thousand years old, full of prison cells and executions and stories; the Palace, five hundred years old, reeking of Tudors and times gone by. If it is evocations, ghosts and memory you seek, these are surely the places in which you’ll find them.

However, here is the thing: for me the Tower was dead (ie ghostless), and only the Palace was alive (ie full of the dead). I love the Tower, it is a great place to visit. If you haven’t been, go. But for some reason to do with me and it, I get no sense of the past. Not really. Cells don’t make me shiver with the reality of being housed in them. I sniff the air for the faint reek of terror and anticipation as any of the poor victims, especially the more or less teenage Catherine Howard, were led to their deaths, and I can’t find it.

In the Palace, on the other hand, the air seemed thick with ghosts. Around every corner the draught felt like the draught that chilled the necks of kings and servants. Even if there was a sign pointing the way to the coffee shop. Even if there were 700 school children in bright yellow uniforms. It didn’t matter. The past was lurking just behind them, was super-imposed on top of them, as if they were being seen through a shadowy film of the lives that had gone before. As if our breath was mingling with the breath of the dead.

It took a long time before I could work out what lay behind this distinction, but eventually I started to wonder if it had to do with domesticity. A place can be old. It can, like the Tower, be home to extraordinary events: the gathering spot of crowds, the place where death swung from the air and showered up red. But that doesn’t, for me, leave any psychic crackle behind, and I think it’s because it’s not actually a home. What I think generates psychic weight and muscle is ordinary life. A place where people have lived for a long time, carried out their day-to-day business, slept, dreamt, woken, died unremarked.

That’s why I think Hampton Court Palace is so super-charged: not because kings visited for two or three weeks a year when it was a place of royalty, but because it became a grace-and-favour residence, where grand old ladies eked out their poverty-stricken final years. Henry VIII wouldn’t haunt the palace: he might have been the owner, but he lived there like a guest. It’s the residents who remain.

Everywhere you go there are traces of their lives. There are nameplates on sidedoors, and long-disconnected bell-pulls. There are baskets attached to pulleys at the top of staircases so that the elderly ladies on the top floor could have their shopping (and, I believe in one case their dogs) hauled up to their level. And clinging to all of this paraphernalia of life, of routine, of the everyday, is the sense of ghostliness: of presence, of inhabitance, of the lingering dead. Ghostliness derived from the domestic, not the dramatic, and all the more powerful as a result.

Or at least that’s the case for me. For others it was very different, and that got me thinking about a related but slightly different topic: what being haunted means for different people. However, to leave you on what passes for a cliffhanger, this issue is one for next time. Will the answers be discovered? Will the root of the ghost phenomenon be established once and for all? Will Lassie save the boys trapped in the abandoned mine? Tune in next time to find out, and in the meantime, have the happiest and most splendid of Christmasses!

Will le Fleming is a novelist. His debut, Central Reservation, is published by Xelsion and

Will le Fleming is a novelist. His debut, Central Reservation, is published by Xelsion and

Leave a Reply